Hi Rick

Thought you might like this early record of a Dovekie inn South Dakota – date probably about 1877. From the Little House on the Prairie Series. Just saw the picture of it in the Blog.

Cathy [Badger]

Cathy Badger has been a long-time birding enthusiast and visited the banding program at Ruthven many times – even though it’s a long haul for her to get there. Some of you might remember her daughter Hannah. This lovely young women spent a lot of time here learning about birds and banding and then went on to get married here in the Coach House. {Somewhere I have a delightful picture of Hannah on that “magic day” when she visited the banding lab in her lovely white gown and….black rubber boots….to see how the banding was going – she had asked us if we could keeping the program going into the afternoon so that the children attending the wedding could see birds up close….we did.}

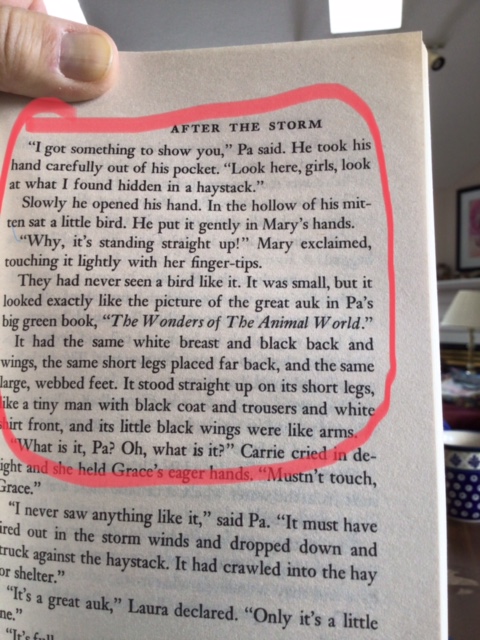

Anyway…Cathy found this true story about a Dovekie that seems to have got blown inland (probably from the Great Lakes) during a storm.

This was a very unusual sighting. It would have been noteworthy for the Great Lakes but remarkable for South Dakota. If it occurred now there would be hundreds, if not thousands, of birders trekking to the site to check it off within minutes of hearing about it. This story about the bird, occurring in the 1800’s, was about as quick as you would have got it in those days.

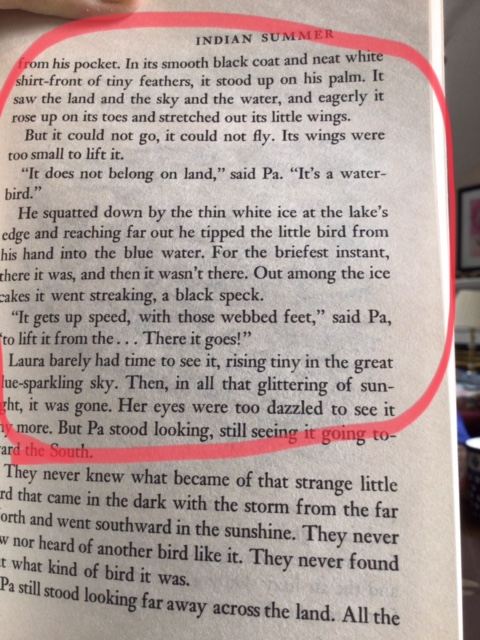

I was interested in the description of the bird’s need to have to patter along the water to get enough lift to take off. “Wing loading” is a term that refers to the bird’s mass in relation to the area of its wings. A bird with a heavy wing loading (like the Dovekie) has small wings for its weight and has difficulty getting into the air. This makes them vulnerable to one of their greatest predators: the Glaucous Gull. I have had a good chance to watch this predator-prey relationship in action while out at sea.

Dovekie in breeding plumage. Note the swollen throat – known as a gular sac – in which it carries phytoplankton from the ocean back to its young at the nest site. Note the boulders, they like to create nests in holes in scree fields. -LJ

When danger approaches – usually the ship I’m on – Dovekies do one of two things: they may dive to escape or they may take flight. When they do what you see is a short patter and then super-rapid wingbeats pulling the little bird up into the air and then, picking up speed, taking off in a direction away from the ship. Taking flight is MUCH easier if there’s a wind blowing as it provides extra lift without any increase in physical exertion.

But it’s at this critical point – lift off and the beginning of forward flight – that the bird is most vulnerable to the gulls. Glaucous Gulls will travel with the ship all day long, effortlessly riding the updrafts created by the ship moving through the air. I’ve watched them do this mile after mile – it’s easy: they’re either right over my head or right beside me. But when we get into Dovekie country (the little birds will concentrate in rich waters) the gulls begin to move away from the ship…on the hunt. They’re searching for a dovekie that chooses flight over diving in response to the ship. If the Dovekie tries to get airborne the gull will swoop in, trying to catch the bird from behind when it’s airborne but has little forward progress. If successful, it’s a quick gulp and it’s all over for the Dovekie and the gull resumes its place over the ship – with an extended crop. But I haven’t seen that many successful hunts. Many times, especially if the Dovekies become aware of the gulls, they will dive. At other times I’ve seen Glaucous Gulls grab a wing but then lose the little bird as it struggles to free itself. When it does, as soon as it hits the water it dives and the gull goes without. But it’s not always easy to see the result as many times the gulls will wander off a considerable distance and I can’t see what happens (although the bulging crop when it returns is a pretty good indicator).

I’ve been amongst nesting dovekies in the massive scree fields at the base of cliffs in parts of Svalbard. They’re sociable little guys and many will often hang out together, sunning themselves on good days, hunkering down out of the wind on others. But….if a Glaucous Gull comes into view, even a long way off, they will either deke into their rocky nest burrows or, as a group, take to the sky.

They’re very sociable birds. They nest in large assemblies (colonies totalling 1 M birds are reported from the Thule area in NW Greenland) and I saw migrating groups in Hudson Strait of several hundred at a time.

Although their population is estimated to be in the millions (one study suggested that there were up to 7 M at the east end of Lancaster sound/NW Baffin Bay during the Spring migration), they do not nest in Canada – in nearby Greenland but not Arctic Canada. The food they require just isn’t found in Canadian waters (or doesn’t show up until too late in the breeding cycle). But a huge number of Greenland birds spend the winter at the ice edge off Canada’s east coast.

Sitting in boulders in a scree field – but always vigilant – searching the sky for marauding Glaucous Gulls. -LJ

Rick