Birding-wise in Malawi I wanted to do 3 things: 1) contribute to the country’s bird atlas by contributing the sightings I made following their atlas protocol to the organizers – In this I have been quite successful: I’ve seen 203 species within a 10-kilometer diameter of the Iris Orphanage. 2) when opportunity arose band as many birds as I could realizing that I would have to be extremely lucky to have one of “my” birds recovered any distance away as there are so few banders in the country and, most people who might recover a banded bird wouldn’t know what to do with it – on this last trip I managed to band 148 birds of 29 species and (really interesting from my point of view) I recovered 10 birds I banded on previous trips (February 2018 or February 2019). 3) In doing these two activities I hoped to involve (or at least interest) some local people in what I was doing- I have been able to involve some of the children in my activities and, when wandering the countryside, have had a number of people approach me to find out what I was doing and I would spend time with them demonstrating how binoculars work and showing them the many birds they might see by using a guide book. Still there’s a long way to go before we could form a local naturalists’ club. But….Rome wasn’t built in a day.

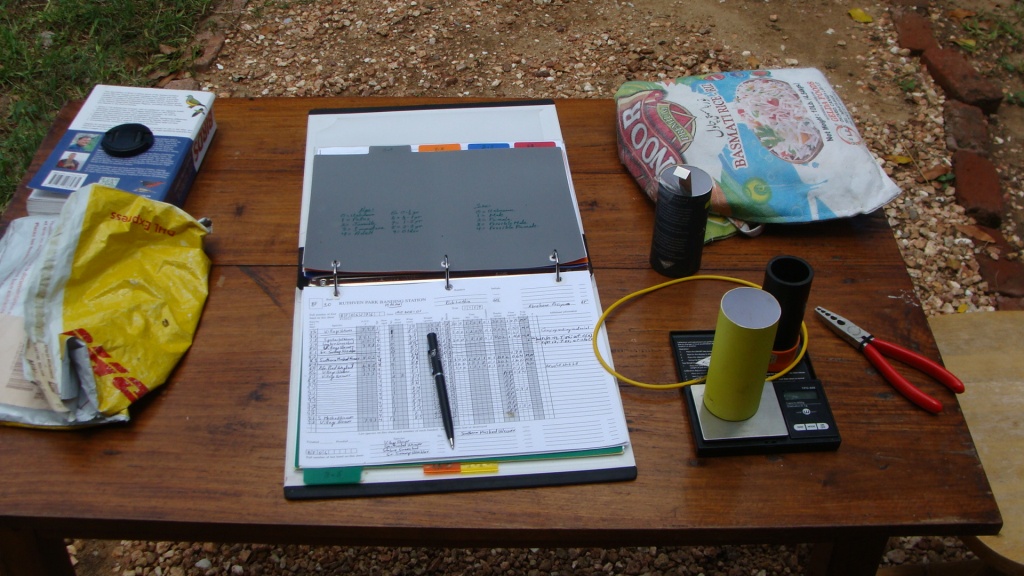

Banding in Malawi (as in Kenya) is a different process than I’m used to at Ruthven. At Ruthven we have set net lanes that we use from year to year knowing that migrants predictably are going to flow through at a particular time each year and will be using the “corridors” (edge habitat) where we set the nets. First of all, in Malawi there are a LOT more birds around, migration or no migration. And where they are and when they’re there is dictated by the rains which can be quite variable. They can start early, or late, last a long time or not long at all, drop a lot of water or, in bad years, hardly any or none at all. So I set my nets based on observations of where the birds are at any particular point in time assessing why they’re there. Usually it’s because of a concentrated food source or an abundance of nesting material. The thing is: these are not constant and can vary from day to day (if not hour to hour – when the fruit on a particular tree is used up then they need to find another tree). Also, birds soon learn where the nets are and begin to avoid them. Consequently, I would move my nets every couple of days and place them where I thought I would get a day or two out of a resource. Fortunately, I was using only 2 nets so this wasn’t a big deal (other than clearing the lanes). The reason for using only 2 nets is that I was worried about a couple of things: a big hit (e.g., a wandering flock of weavers or mannikins could involve a lot of extraction); I didn’t want birds to be hanging in the nets in the heat of the day (on a couple of days the temperature soared into the mid-40’s by mid-morning); I was concerned about predators – birds and, especially, snakes (I encountered a sizeable [1 meter] Green Mamba coiled up atop a shrub next to a net lane – it would be attracted to any bird in distress and I certainly didn’t want to have to try and extract this very poisonous snake- especially when anti-venom wasn’t available).

Due to the heat and intense sunshine, I banded for only 2 to 2 1/2 hours first thing in the morning and then for another hour and a half in the late afternoon/evening. There was less bird activity as well between banding times but I’m sure I could have caught considerably more birds but….at what cost to the birds. As it was, I ended up banding 148 birds of 29 species. Interestingly, I recaptured 10 birds from previous visits. (See the list of both banded and retrapped birds below.) In the future, I would like to “blitz” the area – band with a crew of several people so that we could run more nets in a variety of habitats. Also, I am trying to figure out ways of identifying and then involving and training interested local young people who might be able to carry this on – as has happened in Kenya (with Dan Odhiambo and Brian Ochiago). Isaac Mponya is a young man from Bangula that my colleague Andrew Bremner and I had a chance to work with for a couple of years; he is just finishing off college and is doing a field placement at Majeti Game Park (which I HIGHLY recommend) but whether he will be able to keep going in this field is up in the air. People need to simply survive and this kind of pursuit may not lead to gainful employment – sometimes eating the birds is required just to sustain oneself……

But there’s so much to be learned!!! Very little is known about the distribution of various species within a country; their general movements; intra-African migration/movements; migration between Eurasia and Africa; impact of growing human population and changes in agricultural practices; impact of deforestation; moult strategies; and on and on.

Anyway, here’s some results:

Banded 148 of 29 species:

2 Diederik’s Cuckoo

5 Speckled Mousebirds

5 Red-faced Mousebirds

2 Little Bee-eaters

1 Black-backed Puffback

1 Brown-crowned Tchagra

1 Tropical Boubou

2 African Paradise-flycatchers

6 Red-backed Shrikes

1 Long-billed (Cape) Crombec

1 Green-backed Camaroptera

2 Rattling Cisticolas

4 Acrocephalus Warblers (Great Swamp Warbler??)

3 Sombre Greenbuls

4 Common Bulbuls

2 Pale Flycatchers

1 Black-throated Wattle-eye

2 White-browed Robin-chats

2 Spectacled Weavers

24 Lesser Masked Weavers

6 Southern Masked Weavers

31 Village Weavers

10 Southern Cordonbleus

2 Green-winged Pytilias (Melba Finch)

1 Jameson’s Firefinch

5 Bronze Mannikins

3 Southern Gray-headed Sparrows

18 House Sparrows

1 African Pied Wagtail

Karen’s Kreepy Korner:

Retrapped 10:

1 Rattling Cisticola – originally banded February 1, 2019

1 large Acrocephalus warbler (Great Swamp Warbler?) – originally banded February 2, 2019

2 Lesser Masked Weavers – February 11, 2018

– February 4, 2019

1 Brown-crowned Tchagra – February 14, 2018

1 Pale Flycatcher – January 26, 2019

4 Spectacled Weavers – male; February 18, 2018

– female; February 18, 2018

– male; February 19, 2018

– male; February 5, 2019

Rick